|

Edmund White died June 3, after a long and much-loved life as one of America’s great gay writers. His 1982 autofiction novel A Boy’s Own Story is his best known, a frank and honest story of growing up gay in the 1950s. Many gay men (including myself) found themselves in that book and the ensuing trilogy. He published 36 books including memoirs, autofiction, novels, historical treatments, and the 1977 Joy of Gay Sex. He is a foundation stone of gay English writing. He always saw himself as a gay writer for gay readers, the distinction he drew between his generation of queer writers and those who came earlier, like Gore Vidal and James Baldwin. They might write gay characters, but they never seemed to be writing for gay readers. Ed was. … Edmund White had no use for shame, and in both life and work, he refused to sand down the edges of queer existence to make it palatable. Acceptance was never the point. Truth was. I’ve been mourning his passing these past few days. I didn’t know him personally but his writing and presence have been meaningful to me, particularly as I evaluate my middle-aged gay life. Some suggested reading:

This was also posted to Metafilter

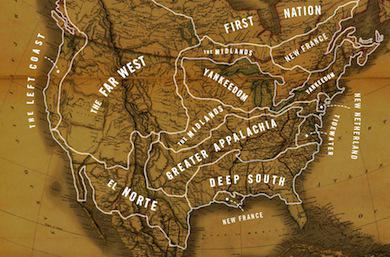

I just finished reading American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, a history and cultural criticism book by Colin Woodward. It’s OK, not great. The map below is the thesis of the book. Woodward argues North America is best understood as eleven separate distinct “nations” with unique cultural and political identities. The first half of the book gives the origins of these various tribes and argues for their inviolate coherence. This part of the book was insightful and interesting. The second half interprets various recent events in terms of a 400 year old conflict between Yankees and Deep Southerners. This part of the book was boring and ax grindy. Related: I’m now an active GoodReads user and am trying to do a better job cataloging the books I read.

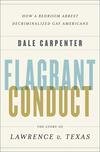

Flagrant Conduct: The Story of Lawrence v. Texas, is Dale Carpenter’s telling of the story behind the landmark Supreme Court gay rights case. The 2003 decision found that people had a right to private sexual conduct and overturned laws criminalizing homosexual sex as well as a previous, damaging Supreme Court decision. Until this decision, gays and lesbians were effectively criminalized in a good part of the US. Carpenter’s book is readable and relevant for anyone interested in gay rights in the US courts, particularly as how it may play out for future gay marriage debates. He does a great job explaining the legal arguments and putting them into the context of the gay rights movement. He also tells the personal stories of the defendants and lawyers, particularly the Lambda Legal team who made the case. There’s a particularly moving description about how the Supreme Court itself had changed since the bad 1986 decision, how many of the justices now knew gay people. The most fun part of the book is all the unknown weird details about the case. Much of this is available in a previous article Carpenter wrote (JSTOR; try your library), but it’s fleshed out more in the book. The defendants in the case, Lawrence and Garner, weren’t lovers and most likely weren’t even having the sex that the arresting officers claimed they were having. They were also 24 years apart and of differing race. All that detail was buried and the defendants were mostly removed from view in order to polish up the specific constitutional challenge that ended up in the Supreme Court. It helped that Texas put up a poor argument for the anti-gay law; the author suggests that the Houston DA’s heart wasn’t really in the case. Reading this book gave me new respect for how hard, expensive, and detailed the fight for civil rights is in the US. We may be endowed with certain unalienable Rights, but it takes a lot of effort to convince the public to not deny them. See also this

Metafilter discussion

Good reading: The Hunger Games Trilogy, young adult novels roughly in the category of Harry Potter but way more interesting. There’s a movie coming March 23 but I worry that it won’t capture the emotional complexity that makes the books so good. So read them! It’s even free on Amazon if you own Kindle hardware and are a Prime subscriber. The setup for the books is not very promising. Future dystopia, subjects are forced to send children every year to a fight to the death for the amusement of the ruling class. It seems like Most Dangerous Game / Running Man / Arena, a cliché action story. And there’s a risk that’s what the movie will be. But the books are so much more. There’s an enormous emotional complexity in the main character, Katniss. She’s a badass hunter and is completely capable of killing her competitors to survive. But she’s also horribly conflicted about it and has a really subtle relationship with her situation in the world. And boyfriends, some good writing there, way beyond the pathetic girly stuff in a novel like Twilight. It’s rare to read something so complex and alienating in books for teenagers. Really well done. The first book is the best but the story payoff in the third book is worth the time.  It took four months, but I finished reading Gary Taubes' masterwork of science journalism,

Good Calories, Bad Calories. If what he writes is correct, this could be the most important popular health and diet book written in a very long time.

It took four months, but I finished reading Gary Taubes' masterwork of science journalism,

Good Calories, Bad Calories. If what he writes is correct, this could be the most important popular health and diet book written in a very long time.

The first half of the book is a long and careful investigation into the science behind diet and the "diseases of civilization": obesity, type-2 diabetes, heart disease, cancer. The conclusion is grim: all our common wisdom is poorly founded. "Everyone knows" that people get fat from eating too much and not exercising enough, that eating fat makes you fatter, and that eating cholesterol causes blocked arteries. But those statements are all scientific hypotheses, not axioms, and it turns out the experimental science doesn't confirm them. Taubes looks in detail at the science and politics behind current government recommendations: low fat diets, exercise and calorie restriction for weight management, etc. And frequently finds problems with the science like inconvenient data ignored, alternative studies dismissed, and personal bias overcoming good science. He also dives deep into the politics. One of the most shocking things is the way public health officials have basically run a giant nutrition experiment, advising Americans to eat low fat diets with no solid evidence that's actually healthier. The last part of the book examines an alternate dietary hypothesis: that carbohydrates are the source of our health problems, not fats. There's research that indicates that the insulin response from eating refined carbohydrates causes your body to store that sugar in fat cells rather than using it as energy, leaving you still hungry but fatter. This metabolic response seems like it could be very interesting for understanding both obesity and type-2 diabetes. If Taubes' book encourages more research in that area, it's a success. The best thing about Good Calories, Bad Calories, and also the most demanding, is how thorough the journalism is. This isn't some hot screed selling a fad diet, it's a boring, meticulously footnoted examination of the actual original science journal articles that led us to our current dietary understanding. It makes for slow reading and a frustratingly muddy final story. But it also feels true, much truer than the platitudes, moralism, and oversimplification that is the usual diet discourse. Definitely worth reading if you are interested in diet and metabolism, or just interested in a detailed story about public policy and science. See also his (much shorter) 2002 NYT article What if It's All Been a Big Fat Lie, this somewhat negative review of the book, and this positive review. Update: it's going against the spirit of

the book to synopsize it like this, but here's the

author's

summary of his conclusions in a short 10 item list.

I'm fascinated by pre-Columbian American history. A whole alternate human history, right here where we live now, different writing and math and technology. And so little known about it! Science journalist Charles Mann's book

1491 scratched my itch to learn more about New World civilizations. It's intelligent but not too demanding, anthropology-lite in the vein of Guns, Germs, and Steel if not as ambitious.

I'm fascinated by pre-Columbian American history. A whole alternate human history, right here where we live now, different writing and math and technology. And so little known about it! Science journalist Charles Mann's book

1491 scratched my itch to learn more about New World civilizations. It's intelligent but not too demanding, anthropology-lite in the vein of Guns, Germs, and Steel if not as ambitious.

Mann's book is written to demonstrate his thesis that New World civilizations were way more developed and technological than our common understanding. He neatly dismantles the idea that Indians were a sparsely populated low impact culture living in harmony with Mother Earth, dismissing it as both racist and not supported by science. Instead in the eleven chapters he presents detailed archaeological research about the surprisingly technological Indian civilizations. Some of the ground he covers includes the continuing controversy over the initial migration dates, the astonishingly urban complex of Norte Chico in 3200 BC and its uniquely specialized economy, and an emerging case that the Amazon rainforest is not some wild pristine environment but instead the result of centuries of deliberate gardening by its inhabitants. The tour of archeology is fun but even better is Mann's explanation about how all of this history is surprising us just now. A big part of our misconception about native peoples' lives is that by the time Europeans met them, 90-98% of them may have died from disease. I'd understood before how smallpox, etc helped the Europeans conquer the New World but I never quite connected our romantic idea of sparse Indian settlements to the fact that, duh, almost all of the people living in the Americas died 1492-1550. He also talks in some detail about the relative lack of physical artifacts from cultures that tended to build with soft, perishable materials. And of course there's also the willful, deliberate destruction of all written records by evil Catholic bishops and the like. If I have a complaint about 1491, it's that when I finished reading it I have an even less clear picture of pre-Columbian history than I did before reading it. The simple schoolboy story is a simple narrative. Now that I've learned more specifics about particular examples the big picture has gone fuzzy. Which may very well be fair and accurate now, given how little we know.  I wish I could remember who suggested

The Steel Remains

(Ian?), because I

simultaneously enjoyed it and was annoyed by its tedium and would love

to talk to someone who really enjoyed it.

I wish I could remember who suggested

The Steel Remains

(Ian?), because I

simultaneously enjoyed it and was annoyed by its tedium and would love

to talk to someone who really enjoyed it.

It's your basic hard-edged fantasy novel, lots of gore and twisted demon sex and noble heroes with dangerous edges. There's some novelty in that the main character is gay and the author isn't afraid to write some hot man/man action (well, man/demon) and explore the irony of being a bad-ass warrior who's loathed for being a faggot. But it doesn't serve the story very well. And the story.. The book never quite goes anywhere, and honestly I never could quite follow all the world-building service and made-up names. (Eskiath, Majak, kir-Archeth, Khazad-dum, Kiriath, Egar; who can keep them straight?) It doesn't help that the book follows the tired narration of interleaving chapters from multiple stories. The novel works best at the end, when everyone is brought together and follows a single story. At the end of the book the author thanks Moorcock for the inspiration of Elric, etc. Which is a nice acknowledgement, but I think I'd rather be reading novels that name-check Delany's Dhalgren for hard-edged gay fantastic fiction. Heck, it's about time for me to read Dhalgren again.  The Discovery of France tells the story

of the unification of France as one cultural identity stitched

together out of the zillion little villages, languages, cheeses that surround

the capital of Paris. It's a cultural history

of France in the 18th and 19th centuries exploring life in the

country before it was truly unified by roads and telegraphs.

The Discovery of France tells the story

of the unification of France as one cultural identity stitched

together out of the zillion little villages, languages, cheeses that surround

the capital of Paris. It's a cultural history

of France in the 18th and 19th centuries exploring life in the

country before it was truly unified by roads and telegraphs.

The author does a great job conveying just how large a country France is and how far-flung places are before travel and communication was easy. The chapter title "O Òc Sí Bai Ya Win Oui Oyi Awè Jo Ja Oua" gives an idea of the author's approach, in this case cataloging the linguistic diversity of various words for "yes" across France. The book is full of amusing anecdotes from travellers, explanations of religions, the role of the Enlightnement and the Revolution in unifying the co untry, and overall a deep love for the French countryside. I particularly liked reading this book as an American. Our vault into modernity comes at the same time as the founding of the country itself; we never had an isolated agrarian past. European history is quite different. I've been reading a lot of books lately. I hope to blog about them

more, reviving a 13 year old

tradition.

I've been enjoying two lovely erotic novels recently, books thoughtful

enough to be engaging as well as prurient. This blog post is safe for

work but the links are generally not.

My Secret Life is a autobiographical novel of a gentleman's vigorous sexual life in Victorian London. The book is mostly an encyclopedic account of various encounters, growing increasingly byzantine as the book progresses. But between all the debauchery is a remarkably honest and sympathetic protagonist. Then came reflection. Had I really frigged a man ... An act I had certainly heard of being done by men to each other, yet all but disbelieved, and looked on as a very foul action yet I had done it, had enjoyed it all. ... It ended in reflecting that I never had intended to do those things, that opportunity had let me unwittingly to do them, and resolving that I would never do it again, I fell asleep.Sometimes he's very libertine, sometimes quite conflicted. There's a lot of interesting class-related observations. The relentless sexual combinations with only slight variation sometimes read like Penthouse Forum letters, but there's enough thought behind it to keep my interest. The book is available free online, I'm reading an abridged edition. The other book I've enjoyed recently is Lost Girls, Alan Moore's porno graphic novel. Obviously not a Victorian book itself, but set in Victorian Austria. Nominally the story is about the erotic hijinks of Alice (of Wonderland), Dorothy (of Oz), and Wendy (of Nevernever Land). The writing doesn't always work, but some of the reimagining of classic childrens' stories are quite good. But as a graphic novel it's not really about the text, it's the art. And the art is a lovely diaphonous dreamworld, mixing eroticism and innocence and vibrancy in a very powerful way. Some good page samples: 1, 2, 3. At $60 it's not cheap but the print quality is beautiful.  I have a great love for Vernor Vinge's

sprawling scifi novel A Fire Upon the

Deep. It's kind of a mess, mixing in so many different plots

and concepts that it's more like three novels. But it's full of

good space opera and flows well. And like the other early Vinge

work True

Names it benefits from a deep well of brilliant ideas: the

singularity, ASCII Usenet as interstellar communications medium,

telepathic doggy group minds, ... I liked that book so much that

every time Vinge publishes a new one I buy it right away and read it.

I have a great love for Vernor Vinge's

sprawling scifi novel A Fire Upon the

Deep. It's kind of a mess, mixing in so many different plots

and concepts that it's more like three novels. But it's full of

good space opera and flows well. And like the other early Vinge

work True

Names it benefits from a deep well of brilliant ideas: the

singularity, ASCII Usenet as interstellar communications medium,

telepathic doggy group minds, ... I liked that book so much that

every time Vinge publishes a new one I buy it right away and read it.

Alas, his new novel Rainbow's End is as disappointing to me as Deepness in the Sky was. It just never quite gets off the ground. The protagonist is an old man rejuvenated by sci-fi miracle medicine, having to adjust to modern technology by socializing with young teenagers. The premise holds promise but the resulting character interactions are wooden and devoid of feeling. The main plot is a mess, something about warring factions and espionage and the menacing but terribly named YGBM technology. But unlike Fire Upon the Deep this mess doesn't ever turn into anything compelling. There are a few clever scifi concepts tossed in but they stick out and are not integrated well. "Hey! Look! I'm talking about Trusted Computing on this page!". I managed to finish the book, but it felt like a duty. I don't normally write reviews of things I don't like; what's the point? But after reading Cory's gushing praise over on BoingBoing I had to offer my own disappointment. That, and I hold out the hope that someone will point out to me that the book is actually brilliant and I'm an idiot. |

||