|

A movie totally worth watching: Around the World by Zeppelin, a semi-documentary of a multi-week 1929 zeppelin flight. Originally a Dutch production titled “Farewell”, the BBC Channel 4 version in English (and on Youtube) is just terrific. What makes the film so marvelous is how much primary film footage they were able to use. The multi-week journal was a press event (funded by William Randolph Hearst) so most of the passengers on board were journalists. Including at least two film cameras. Really amazing to see all this vintage aviation, engineering, and socializing. Another thing that makes the film terrific is the storytelling, drawing most of its narrative from diaries kept by Lady Grace Drummond-Hay. She was a journalist with a fairly sharp eye and pen and her story makes for a nice structure for the trip. Beware the film is partly fiction; some of the events depicted (like an unlikely mid-Pacific repair) did not actually happen. The story itself is just amazing, the history of airships. The Graf Zeppelin comes from a parallel Earth, a time when elegant dirigibles sailed the skies like cruise ships and navy aircraft carriers were airborne. This actually happened, lovely to see it play out in a film. The Graf Zeppelin company succeeded in operating a passenger service for a few years before improving airplane technology and the looming war made airship success unlikely. Not to mention the Hindenburg disaster. There still is a German company operating zeppelins. I flew in the Airship Ventures craft a couple of years ago in the Bay Area, but sadly that company didn’t make it. I haven’t flown a plane in just about a year. I’ve done some trips with Ken supporting from the right seat but I haven’t been at the controls. My biennial flight review is due in ten days and I’m already well past my comfort level with currency and proficiency. How did this happen? The main reason I haven’t been flying is that as cool as being a pilot is, flying a little plane is kind of a pain. It’s impractical transportation. It’s fun to just go up and look around but less so in the Bay Area; the combination of weather and airspace makes a Sunday drive a bit of a challenge. And I’ve already done my $200 hamburger runs to every nearby airport. After my big solo Texas trip I’d sort of met the challenge I had set for myself from the beginning. The related reason is it hasn’t been as fun for me as I hoped. My instrument training stalled out, a common problem with GA pilots; once I’d learned all the fun stuff I was facing lots of hours of grueling practice. I also have never gotten completely over the small anxiety one feels getting in to a little plane. I’m a good pilot and well trained, but the nagging safety concerns in the back of my mind casts a bit of a pall over what should be something just for fun. I feel badly about not flying. I’m privileged to have a license and a medical and a plane to fly and the money to pay to fly it. I know lots of folks who scrap and save and hustle for every flight hour and here I am squandering my opportunity. I’m sure I’ll go back to flying some time, maybe on an Alaska adventure or around Grass Valley where the airspace is simpler or maybe just for sightseeing with friends. It’s just not where my head is at right now. Big patent drama in little business: flight planning software vendor FlightPrep has succeeded in bullying free website RunwayFinder offline with a patent lawsuit. It’s not much different from all the other software patent nonsense that goes on, but what makes it poignant is it’s in the small world of general aviation where we’re all supposed to be friends and where no one is making much money. What follows is my opinion. I'm not a lawyer nor an expert in patent law. I do understand something about software design, though. If this patent affects you, please seek appropriate legal counsel, don't take my word for it. Long story short, FlightPrep got a flight planning patent a few months ago and started going after every other online flight planning service. They convinced SkyVector to license, FlyAGoGo shut down, and they sued RunwayFinder claiming $3.2 million / month in damages. RunwayFinder would be lucky if it makes $500 / month in advertising and seems to be a hobby project for its founder. Rather than risk the lawsuit hanging over him, he shut down. The lawsuit is over patent 7,640,098, a flight planning patent that was originally filed in 2001. It’s a divisional patent that had a lot of trouble being issued, the actual claims that were granted seem to come from September, 2005. There’s lots of prior art: RunwayFinder itself launched in July, 2005 (see also August, 2005). There’s older prior art too, FalconView and AeroPlanner are two names that come up. The patent itself is very specific and I think most software would not infringe. For instance, the primary claims (1, 11, and 21) all contain specific language about “housekeeping frames,” but who uses frames to do anything? The patent also describes lots of other implementation details that do not seem necessary or even a good idea. FlightPrep themselves makes very broad descriptions of what they own, but it’s not what the patent says. Finally, as is typical with software patents, most of the claims granted seem obvious to someone with ordinary skill in the art. The patent appears to me to boil down to “draw some lines between points on a map”. It’s hardly novel to apply line-drawing to aviation maps in particular. RunwayFinder itself was very nicely done, but basically was the obvious “Google Maps for aviation” implementation. Of course none of this armchair analysis helps RunwayFinder; once a patent is granted, you need an expensive lawyer to challenge it. What puzzles me is what FlightPrep thought they’d gain by forcing a small free site offline. My guess is they’re bolstering their patent before going after Jeppesen, the only flight planning company making real money. Then again Jepp can afford lawyers. Update: nailed it! FlightPrep did go after

Jeppesen and AOPA, and Jeppesen has responded by telling FlightPrep

to take

a hike.

Update 2: this story is

getting

some play

and some of the commentary has been quite hostile towards FlightPrep

and Stenbock & Everson, the plaintiffs in the patent suit. While

I'm upset about what's happened to RunwayFinder too, I think it's wiser to

speak respectfully of our colleagues in aviation software. I am hopeful

they will see how fruitless pursuing these patent claims will be, undo

the damage they've done, and go back to concentrating on making products

for pilots.

Update 3:

Flightaware

declined to discuss licensing the FlightPrep patent. FltPlan has

refused. SkyVector has

shared more of their story

about why they licensed.

Update 4: I'm about to leave on a 3 week flying

trip and can't stay on top of this story. No more updates. I expect things to

quiet down, but this story isn't really over until Dave is free of the lawsuit and

can bring RunwayFinder back online.

Update 2011-03-29: After three months offline RunwayFinder is back online with the statement "sat down with FlightPrep and FlightPrep agreed to dismiss the lawsuit! The exact details of the settlement license are confidential."

Update 2012-05-13: FlightPrep sued Jeppesen

in late 2011. Also RunwayFinder shut down in 2011; I don't think it ever really

recovered from the discouragement.

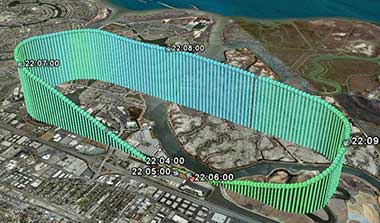

For Christmas Ken gave me a sunset cruise on Airship Ventures' Zeppelin

NT. It was an amazing aviation experience and I enthusiastically

recommend it for anyone interested in aviation or sightseeing. I've

done a fair amount of flying around the Bay Area but nothing approaches

the majesty of an airship gliding through the air at a stately 50mph,

down low at 1000'. And quiet, calm, incredibly beautiful. I took some pretty

good photos.

Zeppelin history is interesting; there was a time when you could

take an elegant three day transatlantic voyage on an airship,

the Empire State Building was built with a mooring mast, and 780 foot

long airships were used as aircraft carriers. (Watch this video of an F9C

Sparrowhawk landing on the USS Macon!) After the heydays of the

1910s–30s zeppelins were almost an abandoned technology, but thanks to

Zeppelin

Luftschifftechnik and customers like Airship Ventures there's hope

for a comeback.

The Eureka N704LZ is the only zeppelin operating in the US. She's fairly small by zeppelin standards, carrying 14 people (compared to the 100–120 people of a Hindenberg-sized aircraft). Airship Ventures is a bold startup, a bet that this class of flight has an important future. They're great for sightseeing and also have businesses training pilots and flying sensor packages. They've raised $10.5M to date. There's a fair amount of ground crew required and the airship itself costs €12-15M. We were lucky to have the founder Brian Hall on the flight with us, his enthusiasm and knowledge was really impressive. The Eureka travels up and down the California coast. We took a two hour sunset tour from Moffett which was fantastic; I think an hour tour from Oakland would be quite amazing as well. We're very lucky to have this airship flying in California; take advantage of it!

The iPad is a very useful gadget in the cockpit. This guide to iPad

hardware and software is for pilots who know more about flying than

computers and are looking to add an iPad to their general aviation toolkit.

Most of these notes apply to the iPhone too. I will update this blog post

periodically as things change. You may also find ForeFlight's

iPad Proficiency for Pilots useful.

What does the iPad do? The iPad is a computer with a revolutionary new user interface. It's ideally situated for the cockpit: easy to use one handed, even balanced on your knee. There's a variety of excellent aviation software for the iPad. It's also a nice companion for Internet while travelling and for entertaining passengers. Electronic Flight Bag plus more. The key aviation software I use is ForeFlight. It contains most everything you need for flight planning in the US: VFR and IFR charts, NACO terminal procedures, flight planning, official weather briefings via DUATS, supplementary weather (radar, METARs, etc), flight plan filing, A/FD, even fuel prices at airports. See their demo video for more. ForeFlight is very complete: I planned and flew an 8 day trip from California to Florida and back entirely using ForeFlight. ForeFlight costs $75 / year for full chart updates for the entire US. An extra $75 for a pro subscription gets you georeferenced approach plates so you can see your actual position via GPS. There are alternatives to ForeFlight with some different strengths: WingX is the best known. Other aviation software. Pilot Wizz and E6BPro are both good calculator/converter apps; Pilot Wizz has a great weight and balance screen. Mr. Sun is a handy little sunset calculator. SkyCharts is a simple alternative for chart display with good enroute display. Jeppesen Mobile TC lets you use Jepp charts, but the app is very limited. OffMaps v1 is a good way to cache street maps for viewing while airborne. MotionX is a nice app for recording GPS tracks to look at your flight later on Google Maps. X-Plane is a fun simulator. I also use a bunch of web pages regularly when planning flights: Fly2Lunch, 100LL, etc. iPad hardware. You have two choices when buying an iPad: how much storage and whether to get 3G. ForeFlight itself takes 6GB for full charts. Double that for updates and a 16GB model is barely sufficient. I suggest buying at least 32GB, more if you want to bring video and music along. 3G is a toss-up. If you get the WiFi only model then it will have no builtin GPS, but see below about external GPS. I like the 3G because it gives you the chance of having Internet access in the middle of nowhere if there's no WiFi. Verizon vs. AT&T is a push, but the AT&T model will work better in Europe. (The original iPad 1 isn't missing anything essential, although the extra CPU speed on the iPad 2 is nice. If money is tight, consider a used iPad 1). GPS. The iPad with 3G has an assisted GPS receiver built in. In my experience it's not useful in the air; some pilots say it works for them but it doesn't work reliably for me. For about $100 you can buy an external GPS. I have a Bad Elf GPS (Amazon) and its performance is excellent, even when the antenna is sitting in the back seat. I've also heard good things about the GNS 5870 (Amazon) and XGPS150 (Amazon) as wireless options. Note that GPS is not necessary to get a lot of value out of the iPad. But if you want a backup GPS in the cockpit or you want to display your position on charts for situational awareness, get an external GPS. Things to avoid. If the iPad overheats it shuts down, a potential crisis if you're flying an approach. Keeping it out of the sun seems to be sufficient although it's worth noting Apple says the iPad only operates to 10,000'. The iPad2 has magnets in the tablet itself and in the case that can swing your magnetic compass from at least 10" away, possibly including when sitting on your glareshield. Do not use the iPad as a substitute for an IFR GPS or for any other required equipment. It is neither accurate nor reliable enough to trust your life to it. That goes double for the apps that emulate an attitude indicator. And of course don't get distracted: if something goes wrong put the toy down and fly the plane. Accessories. People seem to like this clip for knee mounting, also this aluminum case. The iPad battery is rated for 10 hours, so charging in flight may not be necessary. Cigarette lighter chargers work well. Remember that planes are often 28V and the iPad wants to draw 10W. The iPad fits very nicely inside the best flight bag in the world. Alternates: iPhones, Android. For most purposes the iPhone works identically to the iPad; ForeFlight is great on the iPhone too. The big difference is screen size: the phone is too small for plates and working with charts takes a lot of squinting. For alternate tablets I'm hopeful that Android will catch on and offer some competition for Apple, but so far the iPad stands alone. Android requires totally different software; ForeFlight does not have an Android version, but WingX does. Conclusion. The iPad is great for pilots and can replace most of the flight planning you currently do with paper charts and computers. There's a lot of options: my bottom line recommendation is a 32GB + 3G iPad ($730) with ForeFlight ($75/year). If you want a GPS backup, spend $100 on a Bad Elf GPS. Last update October 11 2011

Feedback and updates welcome: email me at nelson@monkey.org

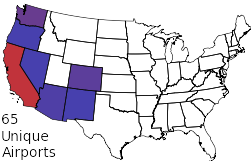

I was playing around with the FADDS aviation database and came up with a report that shows the top 1000 airports in the US as ordered by number of general aviation operations a day. The FAA source data is not entirely accurate but gives a general idea of activity.

No huge surprises: the biggest GA airports are near LA, Phoenix, Daytona Beach, and Minneapolis. A lot of these ops are probably training related; every single touch-and-go practice landing gets logged. I was surprised my little home airport of San Carlos is #71 at 350 ops / day. I have a hard time believing that number is really correct, that's roughly 30 ops / hour of daylight.

Ken and I flew ourselves up to Vancouver for his birthday last week. It was our first international flight in at least ten years, with all the new US security stuff, and frankly it seemed so complicated I suggested we just land in Bellingham and drive across the border. But we figured out all the paperwork and it wasn't so hard after all. There's a variety of detailed guides for flying to Canada (I like AOPA's), here's the gist.

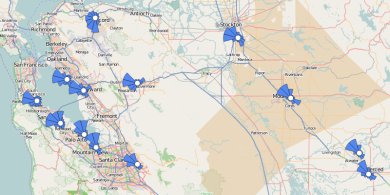

Weeks before the flight we got the plane documented for international flight. Proof of insurance, a radio operator permit for the pilot, a radio station license for the plane ($160), a customs decal ($30). Plus the usual plane documents for any flight. Nothing difficult but it requires a couple hours figuring out government web sites, then possibly weeks before the documents are shipped (ours came in a week). No one ever asked to see anything but the customs decal. The Canadian border is pretty easy. When you arrive, they want a phone call 2 – 48 hours before the flight saying when you're coming. Then on the ground you call again from the customs box. In theory they may come inspect you and your documents, but for us they just gave us an arrival number over the phone. There's no specific border requirement when leaving. The US border is more complicated. The big requirement is filing a passenger manifest with eAPIS for both your departure and your arrival. The web site is awkward (and broken in Chrome), so expect to spend some time. Fortunately you can file days in advance. The eAPIS filing gives you permission to leave the country via email; I also called the local customs office and they seemed confused that I was asking them. You do need to notify customs at your arrival airport 1 – 24 hours before you come back in, mostly so there's someone there to meet you. We arrived right on time and were done in 10 minutes at the plane: radioactivity check (!), passport check, customs decal check. Pretty easy. Flights across the border need to be on a flight plan, both for the US and the Canadians. We went IFR so that was natural; if you go VFR you need a flight plan with a specific squawk code. Canada does charge for ATC services, apparently the bill is in the mail.  I just launched an update on my Wind History project at windhistory.com. The big new feature is month filtering. You can now choose to look at prevailing winds for a specific month or animate a map of the shifting winds over the year. Try it out in the Bay Area, you can clearly see how the winds change in the winter. The rotating Kansas winds are interesting, too.

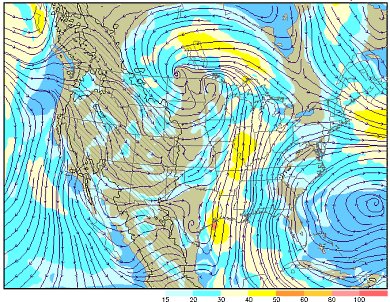

I just launched an update on my Wind History project at windhistory.com. The big new feature is month filtering. You can now choose to look at prevailing winds for a specific month or animate a map of the shifting winds over the year. Try it out in the Bay Area, you can clearly see how the winds change in the winter. The rotating Kansas winds are interesting, too.

I also snuck in a couple of minor changes. The main map page now uses the geolocation API to initially position the map near where you are. And I improved the station page a bit, adding some much-needed tick marks on the radial axis.

Since launching my Wind History map about three months ago, the site has had about 6000–9000 pageviews, or about 100 visits a day. Not exactly blockbuster, but I never expected the site to be a big hit. It's as much a tech demo of advanced map datavis techniques as anything and at that it's a success.

The most popular airports are San Carlos and Santa Fe, no doubt because I use them as examples. Folks are also notably interested in Snyder, TX (from an AOPA discussion); Camp Bondsteel (in Kosovo) and the NAS Whidbey Island and neighboring Oak Harbor in Washington. The nice thing about a static site like this is it takes no maintenance. But I'm playing with some new features now. Geolocation API to move the map to where you are, fancier wind rose diagrams, and static HTML for dumb ol' Googlebot.

I've just launched a project I've been working on for awhile, windhistory.com. Check out the prevailing

winds in California

or see how strong the northeast winds are in Honololu.

One goal of the project is to help pilots understand typical winds at

their airports. It's also a neat demo of what modern web development

technology can do. I'm particularly proud that the wind rose diagrams in

the map are rendered entirely client side in SVG from a single 200k data

file. More tech details in a followup blog post.

Awhile back I wrote

about the religious debate about operating airplane engines. I

finally got a chance to run lean of peak on my recent Texas trip.

Compared to rich of peak, LOP was 20% more fuel efficient, 5% slower,

and about 20° cooler. But I'm still running ROP.

The plane is only now capable of running lean of peak thanks to our engine monitor, fuel totalizer, and GAMIjectors. The stock injectors had one cylinder peaking 1.0 to 1.5gph sooner than others; now our "GAMI spread" is 0.4gph, a win whether we ever run lean of peak or not. On my recent flight I was at 9500', 20.5" manifold pressure, 2400 RPM. Flying at my typical 50 ROP I was getting 140kts TAS, burning 10.3gph, with EGTs at 1357/1378/1352/1324 and CHTs at 303/332/337/290. Leaning out to 40 LOP I was getting 132kts TAS, burning 8.3GPH, with EGTs at 1401/1441/1416/1352 and CHTs at 281/316/311/271. So the difference there is running lean of peak I saved 2gph, ran my engine 20°C cooler, and gave up about 8kts to do it. Saving gas but going slower: is LOP really a win? Cessna didn't publish performance tables for lean of peak, but they did publish tables for saving gas at the recommended 0.5gph ROP. At 10,000' Cessna says full power gives 145kts TAS at 9.2gph. If you want to save 2 gph they have you dial way back on power to get 126kts TAS at 7.1gph, for a 19kt slowdown. So roughly speaking, LOP saves me just as much gas as going slow ROP, but makes me 11kts faster. Despite the good results I still flew over the hard, unforgiving mountains of the Southwest running ROP. The engine feels wrong in the transition to LOP, you can feel the sluggishness. I've also had various salt-of-the-earth mechanics all warn me against running LOP, and while their reasoning doesn't make sense it still makes me nervous. And of course LOP really does make you slower and with four hours of West Texas ahead of you, you want every knot. The cooler operation seems like a real benefit though. (A caveat: those EGT numbers are a bit wonky. The actual measured peaks with some experimenting were 1462/1494/1466/1410 at 8.8/9.1/8.9/9.2 gph, so it's possible I was running more like 90 ROP than 50 ROP and could have saved a bit of gas while ROP. There's some lag in the EGT response time, I was doing stuff too quickly.)

Flying from San Francisco to Las Vegas or other points east is tricky;

between mountains and restricted airspace there are very few ways to

go. The usual VFR route is something like KSQL KWJF KDAG

KLAS, 436nm at 9500'+. That carries you out of the mountains near

Palmdale and south of all the restricted space in California and Nevada.

It gets boring; I recently learned of another route via a desert town,

through the Trona

Gap.

The route is roughly KSQL L05 ODGEE SERUE L72 KLAS, a series of wiggles through a narrow corridor between R-2505 and R-2524. That's 390nm, saving 46nm or about 10% of the trip. The mountains are awfully high west of L05, I'd want at least 10,500' crossing there or else go south towards Bakersfield first to come up the river valley (adds 20nm). Either way it's more time over rough terrain than the Palmdale route, but at least it's something different. I'd only try threading this needle with flight following and a trustworthy GPS. R-2505 and R-2524 are active at all altitudes all the time. R-2506 is only Surface to 6000' during the daytime so you can shave a few miles off the route above. Apparently it's not uncommon to be cleared to enter R-2505 above 10,000' which could save some 17nm. On the other hand the Edwards AFB info says they sometimes close the Trona gap entirely via NOTAM. Plan accordingly. Another alternate route I've flown in the area is via Yosemite, the Tioga Pass, and the Owens Valley. Something like KSQL E45 O24 KBIH O26 L06 KLAS (394nm). It's a fascinating trip through a part of California I'd never seen before and KBIH is a nice stop for fuel and excellent Thai food. Not the simplest route: the Sierra crossing is tricky and wind is a concern both in the mountains and in the valley. Disclaimer: I've not flown most of these routes and have not confirmed altitudes, airspace, etc. The terrain and weather in this area can easily be dangerous. Don't take my word for these route ideas; you're responsible for your own flight planning.

Thanks

to Kareem Fahmi from California Airways in

Hayward for pointing out the Trona route. Kareem also wrote up

a great little pilot's

guide to California airports.

A big part of learning to fly on instruments is procedures: quickly

reading a chart and making the appropriate turns, radio changes, power

changes, etc in the 5–10 minutes you're flying an approach. It's

important to train in a real plane but an instrument student can

learn a lot with a simulator, even a basic PC game.

Simulator: For 20+ years Microsoft Flight Simulator was the gold standard, but Microsoft has abandoned the product and recent iterations like FSX didn't work very well. X-Plane is the new hotness and works on PCs, Macs, and even iOS devices. It's pretty and has neat aerodynamic simulations but what really makes it work for IR training is that it simulates the panel instruments pretty well. CDI needles move smoothly, VORs warble just like the real thing, and it has a good simulation of clouds and the moment of breaking out of them. You can easily customize your plane's panel, too. X-Plane is pleasant software where FSX always felt awkward. GPS: X-Plane has some fancy avionics simulations but the GPS options are terrible. The solution is Reality XP's Garmin 430W/530W. It's a bridge to Garmin's standalone 400W/500W trainer, simulating the most popular high end GA GPS. The realism is fantastic; it feels like it's emulating the hardware and running the actual firmware. The only drawback is the navigation database is from 2007. Not a big deal, but newer approaches may be missing and sometimes it's out of sync with X-Plane's database. ATC: Learning to fly IFR requires learning to work with air traffic control; you can't really simulate that. So enthusiasts have been operating VATSIM, an ATC network staffed with volunteer controllers. VATSIM's quality apparently varies, there's a new modestly commercial effort called PilotEdge that looks promising. Other addons: X-Plane has a robust third party developer community creating model aircraft, better scenery, and various plugin code. Unfortunately X-Plane.org is very poorly organized, hard to find things. I haven't seen anything there I've had to have although I am excited for RealScenery NorCal. There's also rumours of software that imports Google Maps aerial photography to replace the default scenery but apparently it's banned. One neat thing is you can use XPlane's network mode to drive a live display of SkyCharts on your iPhone or iPad. Hardware: X-Plane has a mouse mode but you really need a controller of some sort. I'm reasonably pleased with the Saitek yoke. I also have an older CH Products yoke which is nicely smaller but doesn't feel right. Honestly, neither feel right, I have a very hard time controlling the plane in the pitch axis. I'm beginning to think a fancy joystick would work better, if it doesn't feel like a real plane anyway why not go for something totally different? Getting fancy: There's a whole world of very fancy amateur simulation products. People spend hundreds to thousands on avionics simulations, plane models, scenery, and flight controls. And if you're serious you've got 3–6 PCs networked together running X-Plane so you can look out the side window, too. That's all overkill for learning instrument procedures and for that kind of money I'd start looking into FAA Certified equipment. It may make sense if you want to "fly" a heavy jet, but for my purposes I'm happy with the PC game and then jumping in a real plane.

Flying a plane when you can't see out the window feels remarkably

different than flying visually. When you're in a cloud you never quite

know if you're about to fly into a mountain. All the instrument training

is to make sure you avoid the places where the mountains are, but the

psychology of not being able to see the mountain you know is

nearby is significant.

One key piece of how we stay safe in IMC is air traffic control radar. ATC generally knows where your plane is and helps keep you off the rocks. Often in NorCal the controller gives you vectors, tells you to fly a specific heading for a few minutes while they route you somewhere convenient. Once you're on vectors you are 95% trusting the controller; you're off the charted path. I've been very impressed with the quality of ATC, particularly here in NorCal. But controllers are human and make mistakes, sometimes mistakes that get pilots killed. There's a training crisis in ATC right now, the controllers hired after Reagan busted the union are reaching mandatory retirement and they can't train replacements fast enough. The rate of mistakes is going up. Flying is still very safe but it's in the pilots' interest to look out for themselves. The best defense for a pilot is always knowing where you are. Situational awareness is remarkably challenging with traditional radio navigation, where all you may know is you're somewhere north of a beacon 30 miles away. I'm at the stage where I still regularly get confused: am I west of the airport or east of it? Fortunately my airplane has GPS, a map with a terrain database that shows my position at all times. If I'm being vectored into a mountain, I'll get ample warning. But the FAA still treats GPS as an add-on in instrument flight, an extra, it's not necessary equipment. So we learn how to fly without GPS too. I wonder if I'll ever be truly comfortable flying without my electronic map.

I've started training for my instrument rating. The IR is essentially

the second half of a pilot's license; it lets you fly in clouds when you

can't see the ground and have no visual reference to navigate or even

stay upright. It's a pretty demanding rating and takes about the same

amount of training as the basic private pilot's license. More book learning

than the PPL, so I'm hoping it will go relatively easily.

The other half of the challenge is conceptually understanding where you're going, particularly when flying an instrument approach. You better fly the course right or else instead of being in a cloud in a valley you may end up inside a mountain. The extra workload of dealing with charts and radios means you can't fully concentrate on the instruments. It's amazing how quickly some mysterious force will cause your plane to drift 30° off course and lose altitude when you spend 10 seconds looking at a chart. I've got some 5 hours of simulated instrument training so far and I'm pretty overwhelmed. The solution is practice. Basically a brain workout, training it to be able to handle the extra workload. It'll get easier to keep the plane flying the direction I want. And as I get familiar with approach and radio procedures it will require less thinking to do everything right. Maybe some day I'll even stop confusing my left from right! It's a bit frustrating that half my instrument training is for skills that are on the way to obsolesence. In the real world I'm going to do be doing all my flying with a WAAS enabled GPS and a very capable autopilot, where flying an approach is mostly a matter of punching the right buttons on the computer. But I still have to learn the older radio navigation technologies. And, of course, learn to do it all by hand in case I don't have the fancy gear.

Ken's birthday present was a day's flying in a Cessna Chancellor.

The 414 is a pretty big small airplane: twin turbocharged engines, 6750

pounds, comfortable seating for seven people. It's a small plane

compared to commercial aircraft, but it's big and fast enough that it

can be used for charters. And Ken and I got to fly it. Well, our CFI

flew it, but we got to play along. It's a lot of airplane.

The FAA requirement for me to be legal in the Chancellor is laughably small, 10 hours of flying time to learn how to recover if one of the engines fails. That's a crucial and difficult operation but apparently it doesn't take long to pass the required skill checks. But the MEL is the least problem; I'd need a lot more time and experience before I'd feel safe. And the insurance companies want some 100 hours in a similar plane before insuring a pilot. The main challenge of flying a bigger plane is it has more energy. It's heavier, it's faster, it flies higher. It takes experience, planning, and fine control to go from 200kts at 18,000' to stopped at sea level on a 2450' long runway. More energy is more fun, of course, particularly being able to climb at 1000 feet per minute or more above the Sierras. But everything goes faster, and heavier, and you have to know your plane. The other big challenge is systems complexity. Bigger planes have more stuff: cabin pressurization, de-icing, turbochargers and intercoolers, complex fuel distribution, etc. It all has to be managed by the pilot, mostly manually. Every new task adds pilot workload. The only way to develop that extra bandwidth is experience. The fact that there are two engines out front seems the least of the challenges. There's a bit of extra work tuning the RPMs so they run harmonically but other than that a twin is all gravy. More power. More lift from the prop-wash over the wings. And a great view out the nose with no engine or prop in the way. Babysitting the turbocharger temperatures was more work than worrying about having two engines. As long as both of them are working. I'm not in a hurry to move up to a twin. I just started my instrument rating, that's the next big task. Then more experience flying, only then maybe something bigger and faster.

A funny thing about becoming a pilot; you start hearing a lot more airplanes. With this unseasonably wonderful weather we've had a lot of little planes sightseeing over San Francisco. I used to be barely aware of it, now I hear every one.

It's a little obnoxious. What's hardest is I can't help but listen to whether the engine sounds healthy. Twice now I've run outside in alarm only to look up and realize the pilot just slowed the plane down in order to enjoy the view at a more leisurely pace.

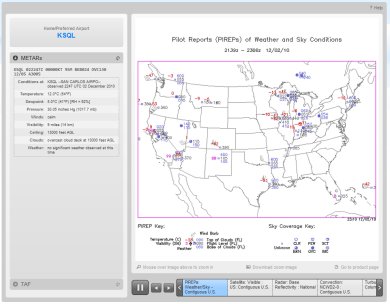

The new weather.aero site is

a great example of government web design done right. Check it out! It's

an experimental version of the venerable aviation weather site ADDS, a joint production of

NWS, NSF, NOAA, and FAA. The new design is great: simple and clean, with

underlying web services to allow mashups with the data. What the kids

these days call "Web 2.0".

My favourite part of the design is how uncluttered it is. The home page contains the key products: a text METAR for home airport weather and a slideshow of weather map graphics showing national aviation conditions and forecasts. The slideshow UI is attractive with a tidy mouseover zoom. Drilling down a layer there's good, consistent page UI for different weather views like winds, radar images, and forecasts. There's nothing revolutionary about the UI but it's very cleanly executed and looks like 2010 instead of the previous 1998esque product. Usable simplicity achieved. In addition to the web page views there's a very interesting web service that lets you easily get XML or CSV data for weather observations, pilot reports, etc. This data has been available for integration before (for instance, via ftp) but this new web service is nicely centralized with thoughtful REST query options like "all METARs along this flight path".The site has modern community outreach, too. The team is on Twitter, Facebook, and has a Nabble-hosted forum. And it's not all faceless bureaucrats, you can even see and learn more about the developers. The US government produces all sorts of amazing software and data. But it's a culture apart from the Internet startup world and, to be honest, has often produced crappy websites. The new ADDS is a different thing entirely, a very nice bit of work. I'm excited to see a new generation of technology produced by government agencies.

Update: I misattributed who built the

experimental ADDS site. The site was built by

NCAR, with funding

and support from NWS, NSF, NOAA, and FAA. NCAR itself is not a

government agency, but rather an R&D center that receives a lot

of federal funding. It's

foundation story is

interesting, a 1960 solution to the same sort of culture gap

I mentioned above.

My airplane has a choke, just like

your grandfather's old Packard. Or as we call it, the mixture

knob. One consequence of GA's antique engine technology is the

mixture has to be manually adjusted during flight. Getting it wrong has

potentially disastrous consequences, yet most pilots have no idea how to

set the mixture. There's even a religious debate about it.

The fuel/air mixture in the engine needs to be in the right proportion, roughly 15:1. If there's too much fuel ("too rich") the engine produces less than optimal power, fuel is wasted and you get carbon deposits in the cylinder. If it's way too rich you can flood and kill the engine, like I embarassed myself in Santa Fe once, but fortunately flooding is not really a risk while flying. Conversely if there's too little fuel ("too lean") the engine also produces less power. Worst case, you can starve the engine and have it quit. This is a flight risk, specifically if the pilot forgets to richen up on descent. You won't notice being too lean at idle power but if you decide to go full power to go around you can kill the engine and, soon after, yourself. The mixture also affects engine cooling. Common pilot wisdom is to fly a little rich of peak because the extra fuel evaporating helps cool the cylinders. If you let the engine get too hot you risk causing detonation or pre-ignition, in which case the engine can run away and get so hot it blows a cylinder. This part's all a little mysterious, particularly in planes without much instrumentation, and mostly we avoid it by trying not to fly over 75% power. The way I was taught to set the mixture was to get to cruise, then lean it out "until the engine runs rough", then nervously push it back in a little bit. High tech! In the past few years engine monitors have become affordable, little temperature probes stuck in the engine that tell you that the exhaust gas is 1475°F and the cylinder head temperature is 332°F. Now pilots can know exactly how hot the engine is running and set their mixture accordingly. You can run at peak EGT, like the manual says, which is efficient but pretty much as hot as possible. Or you can run 50° rich of peak EGT, the common wisdom, only it turns out that places you most at risk of detonation. Or you can run about 30° lean of peak which seems freaky to old timers but definitely saves gas and may keep the engine cooler and cleaner. There's no consensus on what's best, just a religious war, but the guys with the most advanced understanding seem to prefer lean of peak. One more complication: each cylinder stands alone, there's four or six little engines all running in parallel. Each with its own temperature and fuel/air mixture. And there's only one mixture control and it's not properly calibrated between the cylinders. No one noticed this before engine monitors became available so the manufacturers got away with it. Our plane is quite out of balance: one of our cylinders peaks about 1gph sooner than the others so there's no way to set the mixture right for everything. I just ordered $700 worth of fancy GAMI balanced fuel injectors to fix this problem. There's a lot more to say on the topic but I'm out of my depth. The best stuff I've read on engine operation are John Deakin's Pelican's Perch articles. Specifically "Where should I run my engine?" (1, 2, 3, 4). Also Go ahead, abuse your engine!, Mixture magic, and Detonation myths. These articles only present one side, they're the foundational documents of the lean of peak religion, but they're clear and make more sense than anything else I've found.

Ken and I just got back from a 19 day flying trip. Ten days of actual flying, 5900 miles and 48 hours of operating the airplane (average speed of 140 mph; 6 hours spent maneuvering). Took about 500 gallons of gas, 12 mpg. Fortunately I didn't learn to fly because I thought it was particularly practical. This trip was particularly frustrating because we got unlucky with headwinds and maintenance problems.

I am privileged to be able to travel in a small plane. Aside from being able to fly at all, I'm lucky that Ken has such a nice airplane for long trips. And we're fortunate in having the time and money to go on a trip like this and just shrug off a few days' delay. It's unusual for a pilot as new as I to take such a long trip. I couldn't do it without sharing the flying with Ken, both for his expertise and for his instrument rating in case of bad weather.

Here's a map of our full route. My favourite stops were Kansas City for a nice downtown, Cleveland for a great dinner at Lola, and Tucumcari for a small airport fuel stop complete with borrowing a 20 year old cop car to drive in to town for enchiladas. I also enjoyed our time in St. Louis, even if it was frustrating; it's a nice town with a lot to offer visitors. Next up is a trip to Florida for Christmas. Looking forward to not flying through Kansas for once! We may hop over the ocean to the Bahamas while we're at it, would be a nice entry in the logbook.

I'm sitting in St. Louis waiting for our plane to be fixed. This

repair is the third required on our trip to Boston and back. The first

was replacing a vacuum pump in Santa Fe; that only delayed us

a few hours. The second was replacing a gear indicator switch in

Poughkeepsie where we were stopped for a few days anyway. Failure #3 is bad

luck, the attitude indicator failed on Saturday morning.

Mechanics generally don't work weekends and you have to have parts

shipped anyway, so now it's Tuesday and they just installed a new one

and it doesn't work, something else is wrong.

The good news is none of these failures was anything serious; the plane flies fine even without fixing them (albeit it's not legal nor smart). The bad news is repairs are delays, multiple days of delay, and it gets a bit tiresome. The other big slowdown in a little plane is winds. Generally you expect a 10-15kt wind from the west across the US, so you get a tailwind going east and a headwind coming home. But winds change a lot down low and we've had terrible luck. We haven't seen a tailwind yet and half our days have had 25kt+ headwinds, making us travel 20% slower. Between headwinds and other weather our 3 day trip to Boston ended up taking 4.5. At least we're stuck in St. Louis and not somewhere in the middle of nowhere. It's a nice city.

Last September I took my first flying lesson. Partly because I was

looking for something interesting to do, partly to share a hobby my

partner Ken has had for nearly 20 years. Yesterday, a year later, I

achieved my primary goal: to fly Ken in his

plane. The flight went great and Ken didn't even seem too nervous

about me landing his baby. Mission accomplished!

The next big goal is an instrument rating so I can fly through clouds. It's significantly more challenging than the basic pilot's license and I plan to get some more experience before going for it. Right now I just want to get more confident and capable in the Cardinal, really master flying that plane. We've got some big trips planned in the next few months. Me solo up to Portland, also Ken and I to New York and back and then later to Florida (and maybe the Bahamas!).

Flying different kinds of airplanes gets confusing. After flying one plane exclusively for my PPL training I started sampling other kinds of planes. It's been a good experience but I'm ready now to settle down and concentrate on flying Ken's Cardinal.

Every airplane flies a bit different. The three Cessnas I've flown (172SP, 177RG, and 182S) are all roughly similar planes. But each has a different engine, a different feel, and for the 177 extra complexity. The feel is most noticeable when landing. All three planes claim you land at about 65kts. But the 172 feels much slower, is light on the controls, forgiving if you flare a little too high. The 182 is incredibly heavy and you have to drive it nose down until the last second, then haul back quickly (but not too quickly!) while using trim to manage the weight. The 177 is somewhere inbetween and despite the oddity of its stabilator design flares quite nicely. I just got about 10 hours flying the Cirrus SR22 turbo, a Lexus in comparison the various Volkswagens I've been flying. It's fast, elegant, and has a beautifully designed glass cockpit. Really fun plane, I particularly like having turbonormalized power so the plane just flies better the higher you go. The Cirrus is challenging to land, it's faster and heavier than what I'm used to and the tail design means you have to be careful not to flare too much. I found the Cirrus a real handful, it'd take me awhile still before I'd be comfortable flying it solo.I'm impressed with flight instructors who move from type to type every day, flying everything they're in. All planes fly more or less the same, I guess, but I need more experience flying before switching planes. For now I plan to fly nothing but the Cardinal for a few months, get really comfortable in it.

Saturday I had an interesting flying experience taking off on runway

29 at Columbia. I

might well have crashed if it weren't for the instructor with me. Great

lesson.

29 is a grass runway, a rarity in California. I'd trained on soft field technique for my license but I'd never done it for real. The trick is to get the wheels off the ground as fast as you can so you can accelerate better. Because of ground effect you actually lift off before you're going the 55kts or so you need to properly fly, so it's important to push the nose back down towards the ground so that you stay level in ground effect until you accelerate to flying speed. But 29 isn't just a soft runway, it's short. 2600' but with a 1% upslope and a 40' hill just 1200' past the runway end and another hill with trees on it just past that. I've trained on short field technique and thought I was pretty good at it. It's easy enough; you rotate precisely at 52kts, climb at 61kts, and know the math ahead of time for how much distance you need to clear your obstacle. That's all the theory. In practice what happened was we rolled slowly down the runway and the wheels come off the ground just at our abort point. Great, we're airborne! Then I looked up and saw the hill coming at me and freaked out and did precisely the wrong thing, pulling back to try to climb fast. Only we were going so slow that the moment we got out of ground effect the plane would have come right back down again, crashing us in to the hill. Fortunately my instructor has enough experience to anticipate the mistake I was going to make. He immediately took over and did the right thing, the scary thing, pointing the plane's nose down into the hill for a few seconds until we were fast enough to pitch up and climb. He tells me we cleared the hill with plenty of room to spare, I didn't see a thing because my eyes were shut tight. (OK, not really, we were just pitched high enough I couldn't see the hill in front of us. Next time I'll look out the side.) I'm exaggerating the danger for effect, I'm sure my instructor knew all along we would be fine. But I didn't know that and I wouldn't have been fine by myself. I'm well enough trained now that the ordinary flights I do are pretty boring; it's easy to get complacent and sloppy. Great lesson to see the importance of proper technique. It's also useful to learn the limits of your skills. I don't plan to do a soft + short field takeoff on my own anytime soon.

Ken and I are back from EAA

Airventure, 3500 miles and 30 hours of flying. A great impromptu

roadtrip via airplane: not too much planning, just go where we felt like

each day. Our final

itinerary wasn't too far off the rough plan, here's

some impressions from the road.

Day 1: The Western US is really empty. Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, Idaho,

they don't offer much to the air traveller. Cheyenne had the rodeo in

town so we stayed in Casper, a decidedly meh town, decent dinner at FireRock.

Day 2: Downtown Fargo was surprisingly sophisticated. We had a great dinner at the ambitious Silver Moon Supper Club, run by a prodigal son bringing Manhattan-style dining to Fargo. Nice bar, beautifully restored dining room, excellent service, and a well thought out menu. We also liked the lounge at the Hotel Donaldson, a smart boutique hotel. Days 3–8: Wisconsin is surprisingly bland. I like middle America and enjoy smaller towns, but during our stay in the Fox River valley we failed to find anything superliminal. (Airventure itself was awesome, but that's another blog post.) There is excellent Mexican food at Zacatecas in Neenah and the nearby Saint James bar was comfortable. But when the signature local food is deep fried cheese curds you gotta dig deeper. Day 9: Wichita, a last minute decision because we were getting such nice tailwinds. Old Town is an interesting urban renewal project, a warehouse district converted to bars and restaurants and an ersatz town square. It seems to be working pretty well but it was too damn hot and on a Sunday most everything was closed. Wichita is the airplane manufacturing capital of the US: we need to go back with a plan to do some factory touring. Day 10: Santa Fe, my old home. I'd forgotten how mediocre Tomasita's is and regret asking to meet friends there, but we had a good time. Tia Sophia's is still fantastic for breakfast. The cathedral is remarkably beautiful, particularly the light and colourful interior. Day 11: Lake Havasu City is an astonishingly ugly town where despite it regularly being 120° (90° at 5AM) it's full of boaters in summer and drunk bimbos and jocks for Spring Break. We intended just to stop for lunch but got stuck there overnight when the alternator on the plane failed. Actually it turned out fine because all the locals we met were so welcoming and helpful, really nice folks. Desert Skies FBO set us up with a loaner car and a place to stay and Arizona Aircraft Maintenance did a fantastic job getting our plane fixed and us quickly on our way. I'll definitely be stopping here again for fuel and great barbeque, just not in the middle of the summer. We had a really nice time on the trip and I look forward to travelling like this again. Seeing the country in a little plane is a whole different experience; you go faster, you're more disconnected up at 10,000', but then when you land you're suddenly very local.

Ken and I leave tomorrow for Oshkosh, WI and the EAA AirVenture, the Woodstock /

Frankfurt Book Fair / Boy Scout Jamboree of American aviation. It's

enormous, some 300,000 people come every year. The true experience is to

fly in to the

crazy

busy airport and camp on the field in a tent under your wings. Ken

and I have opted for flying in to a nearby airport and staying in a

hotel, more our speed.

This trip will be my first time planning a multiday plane trip. It's complicated finding a route that is safe, efficient, and interesting. The hard part is finding airports where once you land you'll find something to do and a way to get to a decent hotel and dinner. We're planning on three days, stopping tomorrow in Casper WY and the day after in Fargo ND. Also lunch stops in Wendover UT and Spearfish SD. All places I'd never imagined myself going! You can see our full route: 1667nm, or about 15 hours of flying. Weather permitting.The best times in my life have been car road trips where I wasn't quite sure where I'd end up any given day. Flying in your own plane is pretty flexible, but the logistics of finding ground transportation feel a bit confining. Then again for once Ken is the relaxed one about travel plans, he's happy to take what comes to us. Should be fun!

I've finally started training on my real flying goal, Ken's 1978 Cardinal RG.

Ken's had this plane almost 20 years, I'm lucky to be able to fly it.

Ken gave me a key last week! Turns out it's a pretty challenging step up

for a new pilot.

The Cardinal is the Cessna 177; not that different a model from the 172s I learned in. But 172s are designed as trainers, easy to land. The 177 is a travel plane. Every aspect of the design is more aerodynamic, from a cantilevered wing without a strut dragging in the air to the fuel tank vents hidden in the wings, not sticking out in the breeze. It makes for a faster plane (146kts vs. 122kts), but it also handles totally differently. The other change in the Cardinal RG is the RG; retractable gear. I have to remember to put the wheels down every single time I land. I won't die if I forget, but landing gear up makes a hell of a mess and causes the prop to hit the ground, requiring an expensive engine rebuild. I'm doing fine with not forgetting so far, I'm hyper-aware in the new plane. The hard part is the plane flies differently with the wheels hanging out. It adds major drag, like flaps, but without any lift to compensate. If I want to stay level at the same speed I need to add about 15% power. The drag comes in handy, it makes it easier to slow the plane down for landing. And with gear down and full flaps the plane descends quite quickly, helpful if you're too high. On my first simulated engine-out landing my instructor sat quietly while I tried to figure out what to do. I put the gear down first thing, so I wouldn't forget later. Big mistake: the plane dropped so fast I would have landed about 500' short if my engine were really dead. Lesson learned, now I respect the drag from the gear. Ken and I are headed to Oshkosh for the big annual pilot's jamboree. I was hoping to be fully trained in the Cardinal by now so we could share the flying, but maintenance delays and insurance requirements mean I'm going to be a passenger on this trip. I've got a lot I can learn in the right seat, particularly all the fancy avionics Ken has: GNS 430W GPS, MX20 display, STEC 55x autopilot, EDM 730 engine monitor, even the clock is complex. Nice to learn all the systems without the distraction of flying the plane.

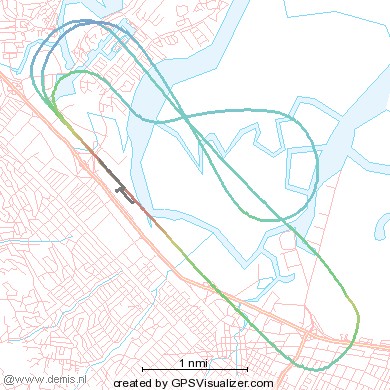

A couple of weeks ago I went on an absolutely fantastic flying trip, a 5

day journey to the Colorado Rockies with the Flyout Group. Normally in little planes

you avoid mountains, cross high and quick for safety. For this trip we

sought the mountains out to enjoy the challenge of flying down in them.

The map above (KML) is from our most mountainous flying, a full day of playing around in the valleys and mountain passes of the Rockies. Some of the highlights include flying through Independence Pass (12,095') and landing at the highest airport in the US (9927'). The 182 we were flying isn't very happy flying over 12,000' and we were breathing supplemental oxygen, but that just made it all the more fun. The main purpose of the trip was instructional: Ken and I had an instructor with us. We got a lot of practical experience with density altitude and performance, learning just what it really feels like taking off at 9000' on a 90° day. We got lucky with calm winds, only 10-15kts at the ridgetops, so we never had to deal with any significant turbulence or downdrafts. That let us fly safely down in the valleys but I'm a little sorry I didn't get more experience with more challenging conditions. Then again we got some very exciting flying with beautiful sights.

It's startling to look under your left wing and see mountains above you! But at a safe distance with good weather, it's fun. See my photo set for more pictures; on the fourth day we flew over Utah along the Colorado River and I got a lot of great overhead shots of Glen Canyon. I also landed and took off at Las Vegas International (very busy), landed in Death Valley (-210'), and took my first flight over the Sierras. A great week of flying, I'm ready for more!

I just got back from my mountain flying trip; 5 days to Colorado and

back. Lots to say about the trip. One thing I learned

first hand was how different it is flying a plane on a 100° day at

9000 feet. It's a little alarming when the plane keeps lumbering down

the runway and never wants to take off. Heck, at Telluride

we took advantage of the fact the airport is up on a plateau; as soon as

you clear the fence you can drop down 1000' into the canyon.

The key idea is density altitude, a measure of air thickness. Little piston airplanes don't fly well in thin air. We need air molecules under the wings to generate lift, oxygen to burn fuel, and airflow to cool the engine. For takeoffs and landings the thicker the air the better: a Cessna 182 needs only 645' of runway to get airborne at sea level but at the highest airport in the US it needs 1430'. Field elevation is the most important thing driving density altitude, but pressure, temperature, and humidity also matter. At sea level when it's 15°C and 29.92inHg density altitude is roughly 0'. On a warm 30°C day it goes to 1800'. When we took off yesterday from the lowest airport in the US it was so damn hot in Death Valley that it was like being at 2600', despite the airport being at -200'. 10°C is roughly 1000' in density altitude. Hot mountain summers require careful attention to plane performance.

The nice thing about flying is you can go directly between airports; no

following roads. But pilots often choose a more

complex route to avoid mountains and in instrument conditions pilots

have to follow specific

airways. There's no signs in the sky, how do we navigate?

Pilotage and dead reckoning are the most elemental navigation. Pilotage just means "looking down", trying to figure out where you are by matching what you see on the ground to what's on your chart. It's remarkably difficult, particularly high up, but following roads and recognizing unusual landmarks works OK. Dead reckoning is the art of guessing where you are by what direction you've been going. It's pretty unreliable, particularly because of winds aloft, but it can give you some idea where you are. Beacons are the historical source of airplane navigation. A VOR radio beacon tells you the bearing to a known station on your chart; cross-checking two VORs (or using DME) gives you location to a pretty precise point. Earlier beacons include NDBs, four course ranges, and beacon lights (map, current operation in Montana). The drawback to beacon navigation is you only learn your position relative to some fixed, expensive-to-maintain equipment. Also it's generally only easy to fly directly to or from a beacon, hard to fly any path. Area navigation is the simplest way to know where you are, X marks the spot. Everyone knows GPS, it makes airplane navigation very simple. Predecessors to GPS include LORAN (RIP) and good ol' sextants, used until the 1970s. An interesting alternative is inertial navigation, in active use today in commercial aircraft and quite accurate as long as you can occasionally correct the accumulated errors with some other reference. I pretty much always navigate via GPS: plug in the course and fly the purple line. But GPS can and does fail, so it's important to stay current with other forms of navigation. Pilotage is fun and keeps you busy long boring flights. VORs are still an important part of IFR flying. But honestly, GPS is so great it's hard to use anything else.

I've finally gotten to use my pilot's license for what I originally

planned: actually going places! As a student I was on a short

leash and since getting my ticket it's been hard to line up a plane

rental, good weather, and the right mood to go somewhere. But this week

has been great: 1000nm of flying, 10 hours.

Monday was a big flight I'd been anticipating for weeks: taking Ken up to Grant's Pass, Oregon to pick up his plane. My first time out of state, my first time over real mountains, and my first time flying over 10,000 feet. The route we took following I-5 never requires you go over 7000' or so, but that's still serious terrain and you get within a few miles of Mt. Shasta, a volcano at 14,200. Unfortunately we weren't able to land in Oregon because there were clouds below us, but I dropped Ken off in Redding to rent a car. Frustratingly the weather cleared an hour later! Today's flight was a classic lunch run to Santa Maria. Nothing too challenging, but a good long distance and a pleasant trip to somewhere different. I finally got what I've been looking for; getting bored in the cockpit. I need to start bringing friends with me on trips like this. (Feel free to ask!) Next week Ken and I are going with a CFI on a group flight to Colorado, 5 days of challenging mountain flying. If the weather allows we'll be doing things like flying through Independence Pass, where the low spot is at 12,093'. And then next month we're flying to OshKosh for AirVenture, probably three days there and three days back again. It's not particularly cheap, fast, or convenient, but it's fun to fly yourself.

The very first radio navigation for aircraft was the Low-frequency

radio range. Marvellously simple idea: a directional radio station

broadcasts the Morse code for A · – to the north and south,

and N – · to the east and west. You listen to that

transmission in your headset. You listen to the station in your

airplane; if you hear A you're north or south of the station, N east or

west. But if you're directly NW, NE, SW, or SE of the station you hear

both A and N overlapping and merging into a single steady tone. Fly that

tone and you're flying in a straight line right to or from the beacon.

Of course the station doesn't have to be oriented to north, the actual

navigation network had some 400 stations in the US defining a network of

airways.

Aviation enthusiasts WWRB have built a working four course range, demonstrated in the video above. Skip to 4:28 for a technical explanation or 7:17 for a demo flight. Four course ranges were decommissioned about 40 years ago in favour of VOR, the system we use today. VOR is the same principle but lets you fly any bearing and uses electronics instead of sound to track the radial.  My first real flight with a pilot's license was Sunday, up to Marysville Airport to

visit nearby Beale Air Force

Base. Beale is home to the

U-2 and

RQ-4 drone; the 9th

Medical Group supports the U-2 pilots with high altitude medical

expertise. Once a month they offer abbreviated

high altitude training to civilian pilots.

My first real flight with a pilot's license was Sunday, up to Marysville Airport to

visit nearby Beale Air Force

Base. Beale is home to the

U-2 and

RQ-4 drone; the 9th

Medical Group supports the U-2 pilots with high altitude medical

expertise. Once a month they offer abbreviated

high altitude training to civilian pilots.

Hypoxia is a real threat to general aviation pilots. Our planes only go up to 15,000 feet or so, but they're almost always unpressurized and often don't have any oxygen on board. Legally I can fly up to 12,500 feet without any supplemental oxygen. That may not be wise, particularly since one of the symptoms of hypoxia is euphoria; you may not even recognize a problem. Our training started with four hours of ground briefing. Then the good part, an hour in the high altitude simulation chamber for a "flight". The hardest part for me was the half hour of pure oxygen through a mask at sea level: a bit of suffocation anxiety. Once we'd lowered our nitrogen concentration in the blood we climbed up to the real test, taking the mask off at 25,000 feet pressure altitude to enjoy our 3–5 "minutes of useful consciousness". The briefers gave us a list of about 10 different symptoms people experience during hypoxia: headache, dizzyness, gasping for air, hot flashes, turning blue, etc. Apparently you get the same symptoms every time. The game is to recognize them in yourself, then turn on your own oxygen. I was doing just fine for about a minute until suddenly wham my vision shut down, everything going grey and collapsing to a narrow tunnel. Scared the heck out of me, I was quick to put my mask back on and everything was back to normal within thirty seconds. Some of the other folks delayed putting on their masks for several minutes, either wanting to get the most from the experience or out of pure belligerence (another hypoxia symptom). Overall it was a good trip and I'm thankful to the Air Force for providing such expert training to GA pilots. I think I know more about handling rapid decompression than the creeping hypoxia that's the real threat to me, but hopefully I'll know now to recognize when my vision starts failing or my fingernails turn blue.

It was such a long time coming I forgot to blog that I got my pilot's license last Thursday. My check ride got postponed three times for weather but I finally got it done. Not my best flying that day, to be honest, but safe and up to the standard. Very happy and proud to have it done.

All told it took me six months to be ready for the private pilot's license: 80 hours of flying and 120 hours of my instructor's time. I could have done it in less time if I'd been more focussed. But all the learning was fun and I figured now was the time I was going to learn how to fly the most efficiently, so might as well do some extra training at the start. Learning to fly is the first time I've been aware that I'm old enough that it's hard to learn new tricks. (Rule of thumb: 2x your age in hours to get the license). I now have two main privileges over being a student. I can fly anywhere without an instructor's signoff and I can take passengers. I haven't flown since the check ride, but if this crazy weather permits I'll do a little trip to Salinas tomorrow. I'm eager to do more serious cross-country trips, overnights travelling 400 miles or so. Reserving rental planes makes it difficult to go on short notice. What next? Flying has all sorts of merit badges one can earn. The first thing I want to get is my complex rating so I can fly Ken's Cardinal RG. I'll also need a bit of instruction in that plane and probably some more hours just flying before I'm comfortable moving up to it. Ken and I have two flying trips planned this summer: mountain flying in Colorado with a flight instructor in June and heading out to AirVenture in OshKosh in July. Mostly I just want to fly a bunch of cross-country trips. Down the road I hope to start training for my instrument rating; that's kind of like the second half of a pilot's license, the ability to fly in bad weather.

Air traffic control has a pretty

good picture of where all the airplanes in the sky are. The technology

for finding airplanes is remarkably complex and varied and is in the

middle of some significant

upheaval. Plane location tech has been under development 50+ years

and is slowly evolving from a centralized, radar-based system to a

peer-to-peer GPS-based system. It's kinda neat.

Radar is the primary way ATC finds planes. Tracon facilities have a network of radar installations, each updating every 5 seconds with a range of roughly 60 miles. Radar tells ATC where something is but not what it is. So to augment radar, most planes also actively transmit data with a transponder. Most little airplanes have a Mode A/C transponder operating at 1030/1090MHz responding to broadcast queries with a simple digital encoding. Mode A queries are answered by the plane with a 12 bit squawk code. I usually fly with the anonymous code 1200, but if I'm getting ATC services they assign me a unique code. A Mode C query is answered with an altitude reply to the nearest 100 feet. (Awkwardly, there's no distinguishing a Mode A reply from a Mode C other than context). Mode A/C responses were designed to be received solely by ATC, controllers verbally tell pilots where other planes are. Recent fancy TCAS systems can listen in on the transponder traffic to show plane locations in the cockpit, there's even inexpensive portable receivers for mode C data. Mode S is the current state of the art used by commercial aviation. It's 1030/1090MHz as well but with 20 or so different responses of up to 112 bits each. Planes can be individually queried by their unique 24 bit address. Planes also can continuously broadcast their GPS position and velocity on an extended squitter. Mode S equipped planes usually receive TIS data from the ground which basically lets the pilot replicate the plane location display the controller has. The new hotness is UAT, a system designed around peer-to-peer communication and flexible data protocols. Planes broadcast their GPS position and velocity for reception by anyone. Other planes and ATC listen in. UAT also includes significant data services like weather radar images. UAT is still not quite finalized, but the FAA has a plan for coverage. An interesting alternate technology is FLARM, an unofficial transponder system developed by enthusiasts in Europe. Basically glider pilots got sick of waiting for someone to make a collision avoidance system that'd be cheap and light and low power, so they built their own. It's conceptually similar to ADS-B but simpler and has been a rare hacker-style success in avionics. Mode S and UAT are two implementations of ADS-B, the FAA's big plan for the future of ATC. There's a lot of politics about the two competing techs: UAT is newer but commerical airlines already implemented Mode S and don't want to pay to upgrade. A final ruling is overdue but it looks like the FAA is going to bless both systems with ground repeating stations translating data. The interesting thing to me about this is how we're slowly moving from a ground-based surveillance design to a cooperative peer-to-peer system. (The shipping industry is ahead of aviation, with some pretty cool apps). A key enabler of this transition has been better radio signal technology so that little planes can be two way communication nodes in an airborne network. GPS is also essential, knowing exactly where you are is a big deal. There's a lot of ugly detail in the specifics, but those details are interesting responses to limitations of older technology. Thanks to Wikipedia's aviation community, their

articles are good

I have half a pilot's license. My checkride was yesterday at Castle. I did great on the

oral exam but decided to postpone the flying portion because the winds

got too strong (17-25kts). Same thing forecast today, so now I'm in

limbo hoping to finish the exam next week. Grr!

Planes drift with the wind. You can't really feel a steady wind, all you

sense is your speed over the ground changes. My plane goes about 120kts

and winds are typically 10-30kts, so my real speed is ±25% which

makes a big difference for fuel planning. A crosswind also pushes you

off course, so you have to

calculate wind corrections. Easy

when travelling straight, but one of the checkride tests is flying

a perfect circle around a

landmark. Not easy with a 20kt wind blowing you off course.

Steady winds straight down the runway present no problem, if anything they make it easier to takeoff and land. Winds blowing across the runway are a different matter; difficult crosswind landings are something every pilot respects. Coming home yesterday I landed in a 10-14kt crosswind at San Carlos, but it took me 3 tries. The biggest problem with strong winds is they're seldom steady. If a wind is 10kt gusting 20kt, your airspeed may suddenly drop 10kts in a lull. That can be a problem if you're flying slow near stalling speed. And gusty winds require active flying to stay pointed the right way. San Carlos has a bunch of mechanical turbulence from the wind swirling around the buildings near the runway. Crosswinds there don't just mean a static correction, you have to sit up and dance fast on the controls like you're playing a videogame. It's kind of fun but very demanding.

Pilots in the US have a lot of freedom. I can fly pretty much anywhere

and land at pretty much any public airport without asking permission or

even telling anyone. If air traffic control is involved it's generally

to help me avoid other airplanes, not to tell me where I can't go. There

are some general rules for safety (at least 1000 feet over cities, for

instance), and some restricted

areas and special rules over places like Washington DC. But pilots

are basically free to go where we want.

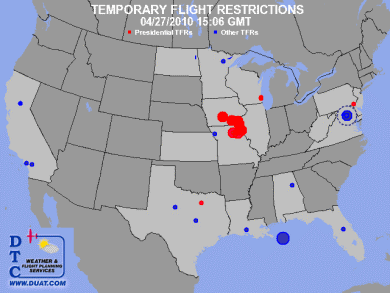

But there are Temporary Flight

Restrictions. Most of these are one day restrictions for specific

events. The blue dot in the Gulf of Mexico is because of the

oil spill: only Coast Guard below 4000 feet. The red dots around

Iowa are for Obama's visit:

can't get within 30nm of his stops. The little dot in

Dallas is for George W. Bush, just 1nm under 1500 feet where it's

probably not a good idea to be flying anyway. Most of the TFRs are

safety or security related and seem reasonable, although it's rough

on business when Obama is vacationing in Hawaii.

Then there's the weird ones. There's been a "temporary" flight restriction over Disneyland since 2003. Why? The 3nm buffer doesn't provide meaningful security; the cynical theory is it stops banner towing. There's also a blanket TFR for sporting events: no flying over large stadiums during baseball, football, Nascar, etc. I don't want to be the jackass buzzing the big game. But it's pretty difficult to know where every stadium is (not all charted) and know the schedule of all major sporting events in the area. Pilots have a pretty good deal in the US, I'm prefectly happy to have some limits for everyone's safety, security, and comfort. I just hope we don't keep expanding the restrictions to make a complex mess that pilots can't understand.

From FAA Advisory Circular 00-6A, "Aviation Weather For Pilots and Flight Operations Personnel". All that's missing from this groovy illustration is the cocktail glass in the pilot's left hand.

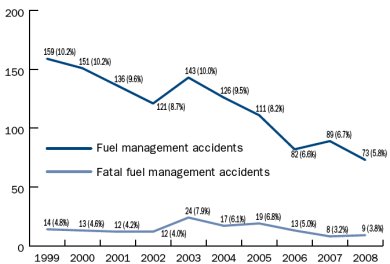

One of the silliest, most preventable reasons for a small airplane to crash is

running out of gas. It happens with some frequency. Why?

Plane design doesn't help. Old airplanes typically have a float fuel gauge whose only standard of accuracy is "reads correct when empty". It's not uncommon for the gauge to read 5-10 gallons wrong. So before every flight I climb up to the wing and put a calibrated dipstick in the tank. And many airplanes require the pilot remembers to manually switch tanks or activate pumps in flight. Some 30% of fuel management accidents have the plane running out of gas while there's still gas in the tank. The primary way GA pilots manage fuel on board is to do arithmetic. You look at the length of your trip, the winds, read some performance charts, then bust out your calculator to figure out how long it will take you to get to your destination at what fuel burn. I might get anywhere from 10 to 18 miles per gallon on a flight. And if the headwind is stronger than I expected or I'm routed the long way, it might take more than that. The 30 minute required reserve is really not enough.

Fortunately the fuel accident trend has been improving. There were twice as many fuel management accidents ten years ago. Part of the improvement is education, part is technology. Aviation GPSes do a good job of estimating and displaying your range with available fuel. And fuel totalizers can very accurately measure how much fuel you've consumed. Still you have to know how much gas you had in the first place, a remarkably difficult thing to determine.

One of the reporting points we use when flying around the Peninsula is SLAC,

officially

VPSLA,

the Stanford Linear Accelerator. It's a 2 mile long

straight line on the ground, very easy to see, and it's at a convenient distance from the San Carlos and Palo Alto airports for calling in to land.

I'm sure there's some rational explanation for why a high energy physics installation 2000 feet below me would cause my VHF radio to pick up random signals. But aviation is a faith-based enterprise, not science, so when I hear the creepy noise I just whisper "4 8 15 16 23 42" to myself to keep the plane from falling out of the sky.

One of the fun things about flying is you get to accessorize. Bags, electronic gizmos, etc. Here's some products that I've found helpful. Some of this is flying specific, but not all of it.

Another fun flying lesson today, spin recovery training. A

spin is a

terrifying

flight maneuver where the wings are stalled, you're pointed down towards the

ground, and the plane is spinning out of control about once a second. You never

want to go anywhere near a spin in ordinary flight, it's a good way to end

up dead fast. But in the right plane with a pilot who knows what he's doing

a spin is kinda cool.

Spin training is a bit controversial in flight instruction. It's no longer required because too many students (and instructors!) killed themselves trying it. And spin recovery training isn't clearly useful; the most likely circumstance where you'd spin by accident is at takeoff or landing where you won't have enough altitude to recover anyway. So flight training is focussed instead on recognizing when a stall is about to occur and recovering before a spin ever develops. But I wanted to try spinning to get a sense for what's over the horizon, how much further you can push a plane and live to tell about it. Also, spinning a plane turns out to be super fun. Queasy, dizzyness-inducing fun, like a rollercoster. But I have new confidence having learnt how to recover from a challenging flight condition. I hope never to spin a plane again, but now I know what it's like. The most fun part of my lesson turned out to be flying the Super Decathlon, the aerobatic plane we used for spin training. I've been learning in Skyhawks, the minivans of aviation. Big, comfortable, good for travel, and mushy clumsy handling. By contrast, the Decathlon is a little sporty coupe. My first turn surprised me; I was only beginning to think about turning when we were already in a 30° bank just perfect for making that turn. Very fun flying something so nimble.